Sutton Coldfield's Evolving Identity: From Royal Town to Uncertain Future

On a dreary Monday morning, crossing Chester Road beneath the ornate sign welcoming visitors to The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, I'm returning to the place I still consider home despite leaving in 2008. This journey holds personal history—my grandparents made a similar transition in 1956, moving from Erdington to what was then an independent Warwickshire borough, seeking better prospects just as previous generations had done.

A Town Transformed: Losses and Contradictions

Seventy years later, Sutton Coldfield presents a complex picture of change and contradiction. Since being absorbed into Birmingham in 1974, the town has experienced what many describe as a prolonged identity crisis. The retail landscape has dramatically shifted, with the departure of major stores including the symbolic loss of Marks & Spencer in 2019 from its once-grand premises—a move locals say "ripped the soul" from the town centre.

Beyond retail, Sutton has witnessed the closure of its main library, the disappearance of its night-time economy with seven or eight bars and clubs vanishing from The Parade, the loss of two local newspapers, and the conversion of surrounding countryside into developments like the enormous Amazon warehouse. Paradoxically, while experiencing these losses, Sutton has become more exclusive and expensive than ever, with former council houses on the Falcon Lodge estate now commanding prices exceeding £250,000.

The Development Dilemma: Plans and Paralysis

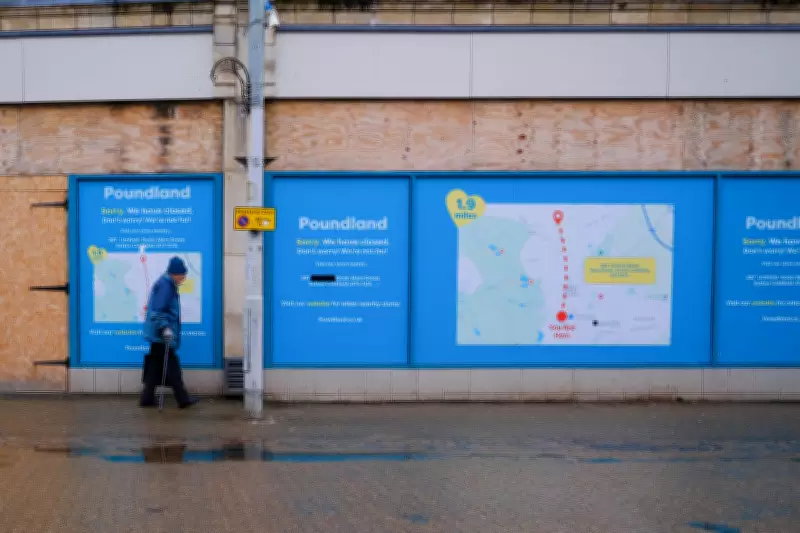

The town centre presents a particularly stark picture of decline. Walking through The Parade and the 1970s-built Gracechurch Centre, one encounters boarded-up shops like the former Poundland with its faulty alarm creating an eerie atmosphere. "Wants a bomb dropping on it" was a common sentiment about the area among regulars at The Duke pub where I worked in my youth—and twenty years later, you might believe that bomb had indeed landed.

Architectural designer James, an old schoolmate, describes the situation as "managed decline," a term more commonly associated with 1980s mining communities than Sutton Coldfield. He explains that short, unfeasible leases offered to potential tenants—sometimes as brief as three years—indicate property owners aren't genuinely seeking occupants. The proposed solution involves transforming Sutton into a "living centre" by breaking the restrictive ring road, opening up the hidden river flowing beneath the town, and replacing outdated large retail units with buildings better suited to modern business needs.

Community Perspectives: Division and Hope

Local perspectives reveal both division and glimmers of optimism. Jack, landlord of Sutton's oldest pub The Three Tuns since 2018, expresses frustration with the Business Improvement District (BID), describing it as "a tax" that provides little benefit to businesses outside The Parade area. He's witnessed the dramatic decline of Sutton's nightlife firsthand, noting that "kids today don't drink" but prefer vaping and fast food.

Yet hopeful developments exist. Everyone mentions Silver Tree Bakery's recent opening in the Gracechurch Centre as a success story, and nearby areas like Boldmere demonstrate how once-declining shopping rows can transform into thriving mini-centres blending independent businesses with popular coffee shops. Similar revitalisation is occurring in Wylde Green and Mere Green, suggesting that while the town mourns lost institutions, residents who can afford to remain actively support local entrepreneurs.

Political Dimensions and Social Change

The political landscape adds another layer to Sutton's identity crisis. Zoe, a community activist who moved to Sutton from North London twenty years ago, observes that while the town remains predominantly Conservative and has "never not been Conservative," she believes it has "become more right-wing" in recent years. She points to the appearance of flags in working-class areas and weekly protests outside a former hotel in Wylde Green currently housing asylum seekers.

Zoe highlights the contradictory responses to local refugee support work, noting that while James Sullivan of St. Chad's Sanctuary recently received a BEM for his work with refugees, neither the town council nor MP Andrew Mitchell have publicly celebrated his achievement. "I think there's a bit of a fear—and a lack of leadership," she suggests, gazing at the MP's office with its flaking blue window frames.

Green Space Controversies and Housing Pressures

Development pressures extend beyond the town centre to Sutton's surrounding green spaces. Plans for thousands more homes—almost 80% of those earmarked for Birmingham's greenbelt—threaten areas like Newhall Country Park. Zena, a lifelong resident, declares she'll leave if 300 homes are built just five minutes from her doorstep, calling the park "the only reason I've stayed."

This resistance to change echoes through Sutton's history, yet change has been constant. I recall a photograph of my mother in my grandparents' garden during the early 1970s, with distant fields visible behind her. By the late 1990s, those fields had become the housing estate I walked through to school—the same estate where Zena now lives.

Uncertain Future: What Comes Next for Sutton?

As I leave Sutton Coldfield, traveling up Birmingham Road the way my grandparents came, I'm left with more questions than answers about the town's future identity. The shadow of that metaphorical bomb regulars wanted dropped on the town centre decades ago still looms, but its eventual impact remains uncertain. With plans for extensive housing development, continued retail challenges, and political complexities, Sutton's identity in ten years' time is difficult to predict.

The social mobility my grandparents achieved through my grandfather's wage from the Dunlop factory—enabling them to raise a young family in Sutton—now seems like a relic of a different century. As a fellow Sutton expat once told me, "It's a strange feeling, knowing you'll never afford to live in your hometown." Today, I understand exactly what he meant. Sutton Coldfield continues to trade on its royal status and desirable postcode while offering less to residents and facing an uncertain regeneration path that divides community opinion and tests political leadership.